Companies are using online activity to determine credit ratings adding to fears about privacy

W

hen browsing the internet in China, be sure to avoid logging on between 2am and 4am, steer clear of websites offering quick loans and beware of changing your mobile phone handset too often. A good rule of thumb is to order curtains for your office, and when shopping online, choose scuba gear over photographic equipment.

The reason? All of these choices may be affecting your credit rating. And your credit rating, as determined by a number of experimental algorithms being tested by China’s largest internet companies, may one day affect a lot more than your ability to get a loan — some believe it could determine your access to health, education, employment and status as a “good” citizen.

The new rating systems are part of a government-backed effort to increase lending to hundreds of millions of Chinese who want access to small business loans or consumer credit, but have no collateral or financial history.

To address this, companies offering everything from business loans to credit with retail stores are relying on “non-traditional” indicators such as internet search histories and mobile phone purchases to help determine who is creditworthy. Private corporations admit they can access the records of Chinese internet users thanks to licences issued by the central bank last year to develop experimental credit ratings.

So far, eight licences have been issued to companies ranging from Tencent and Alibaba, two of the biggest internet conglomerates, to Ping An Insurance, one of China’s largest insurers.

These credit scores are becoming the gateway not just to loans, but to an increasingly wide range of non-financial activity. A higher rating can give you access to the fast lane in airport security, swifter approval of foreign visas or even help in adopting a pet.

A separate initiative by Beijing intends to use algorithms on all this data to rate not just citizens’ creditworthiness, but their overall “honesty” and “trustworthiness”, by as early as 2020.

So far, the government’s efforts are largely theoretical. No one knows exactly what the new models will look like or what variables will be employed. An opaque draft of the plan says the intention is to “use encouragement to keep trust and constraints against breaking trust as incentive mechanisms,” and spells out the objective to raise “the honest mentality and credit levels of the entire society”.

Wang Zhicheng, a professor specialising in credit risk at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, says the project is borne out of a “crisis in ethics” in today’s China. “People don’t think that credit or integrity is important,” he says. “That is what the [broader state] system is intended to do — raise the cost of unethical behaviour.”

However, he says, rating people on their big data may not turn out to be easy — China’s internet is rife with fake data, profiles and transactions.

“China has a long way to go before it actually assigns everyone a score. If it wants to do that, it needs to work on the accuracy of the data. At the moment it’s ‘garbage in, garbage out’.”

Lab rats

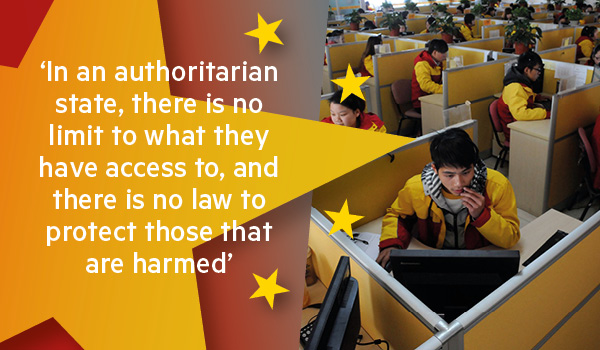

Critics say China’s internet is fast becoming a laboratory where big data meets big brother, where the march of technology combined with profit-driven private companies, authoritarian politics and weak civil liberties is creating a toxic cocktail. If unchecked, the “social credit” system, according to some, could be used to assign citizenship scores to everyone based on “patriotic” criteria such as whether they buy imported products, or the content of their postings on social media.

Anne Stevenson-Yang, head of J Capital Research, a Beijing based consultancy, says the system appears to be aimed at a key goal articulated by President Xi Jinping of fostering greater social control and public morality.

In a research note, she argues that the goal of “social credit” scoring is to return China to levels of personal surveillance common between the 1950s and the 1970s, when everyone had files maintained by their work units under Mao Zedong’s regime, and busybodies in every neighbourhood kept authorities informed of the minutiae of daily life.

Greater mobility and decentralisation mean that the country’s “dangan” system is no longer the complete cradle-to-grave record it once was, but the big data being gathered by the leading internet groups on China’s web users, which numbered 668m according to the government’s latest estimate last year, may turn out to be a close substitute.

Harvesting this data has become a priority for Beijing. Local district administrations have set up “data co-ordination bureaux” aimed at being “a combination of post office and data pool”, according to the state-run Xinhua news agency, where dozens or even hundreds of databases are centralised.

“I think there is a sense in [the Chinese] government that all this data is being generated on people’s mobile phones ... and smart watches and the government thinks ‘Hey, I want some of that’,” says Rogier Creemers, a lecturer on Chinese politics at Oxford university.

Government security agencies already have a vast array of internet censorship and surveillance apparatus known as the “Great Firewall”, which monitors and blocks social media posts about ethnic troubles in the northwestern province of Xinjiang, or the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Mr Creemers insists it is too early to judge the new “social credit” system that appears to combine mass surveillance with algorithms aimed at establishing correlations between social behaviour and internet data. He says it is unclear whether there is any link between the government’s project and the experimental private sector credit rating efforts under way by Alibaba’s Sesame Credit and Tencent.

‘Good people’

There are many questions about what goes into the private credit scores. China Rapid Finance, a peer-to-peer lender which calculates credit ratings using Tencent data, says it uses online purchasing data to determine creditworthiness. According to its scoring system, scuba gear is good, while photography equipment is bad. The smartphone app for Alipay, Alibaba’s payments affiliate which runs Sesame Credit, tells users that the airline tickets they buy or hotels they book online influence their score. In addition, it says “we will consider your overall influence in your social connections circle and the credibility of your friends” in determining the score, which goes up to 900.

A spokesperson for Ant Financial, Alipay’s parent, denies that a friend’s rating will “impact your own Sesame credit score”. But a senior figure at a second Chinese internet company indicates that an individual’s online links are fair game in rating users.

“We can assume good people are friends with good people,” says a senior figure at a Chinese internet company, when asked to explain the credit rating algorithms, “and credible people are friends online with credible people”.

The lack of public information on the private companies’ credit rating algorithms has aroused the curiosity of analysts, who question whether the systems will be any good at their primary purpose — predicting defaults.

“When I say credit rating, I think of the ability to repay a loan. Some of these companies seem to see the goal as more broadly defining the character of their users,” says Mark Natkin, head of Beijing -based Marbridge Consulting.

Mr Creemers says the credit rating system represents a melding of two

utopian visions: that of Silicon Valley and that of the Chinese Communist party.

utopian visions: that of Silicon Valley and that of the Chinese Communist party.

“The Chinese government, Chinese internet companies and Silicon Valley seem to share a commitment to paternalistic improvement of the human condition,” he says, citing a quickly expanding literature epitomised by Nudge, the 2008 book that argues technology can create largely undetectable incentives for people to improve.

“In both Silicon Valley and in Beijing, there is this notion that we can use technology to shape and reshape incentives in such a way that people will behave better. And ‘we’ get to decide what we mean by better,” he says.

Melding pot

China’s social credit system, argues Mr Creemers, is an extreme example of what starts when a smartphone rewards its owner for taking the stairs instead of an elevator, or users rate others to become a “trusted reviewer” on the travel website TripAdvisor.

China is not alone in wanting to tap into the surveillance power of the internet. The 2013 revelations of Edward Snowden, the US whistleblower, exposed the involvement of American companies and intelligence agencies in programmes that gave the government access to personal data. US credit rating agencies have experimented with using internet data as indicators — such as where someone shops — that according to some have become akin to the outlawed practice of “red lining” borrowers according to their neighbourhood.

The growing distrust of Google, Facebook and other tech groups in the west highlights the unease surrounding the amount of personal data these companies hold . In China, the merger of big data and big brother is even more ambitious, say analysts, taking place in a legal vacuum and by an authoritarian state with no civil protections on privacy.

“On the outside this system may seem like a way to promote trust and credit worthiness and is supposed to be progressive,” says Hu Jia, a Chinese activist and dissident. “But in an authoritarian state, there is no limit to what they have access to, and there is no law to protect those that are harmed.”

Some of the companies involved — many with global reputations to protect — are taking precautions. One executive from a company that received a credit rating licence says frankly: “There is no clear regulation in China yet [about the] kind of data a private corporation can access and what you cannot use.”

The executive says his company has access to a vast trove of mobile phone records as part of a partnership with Chinese telecoms groups, and faces no legal restrictions on their use. But he says the company has chosen not to collect this data due to internal concerns over privacy.

“The standard we apply is more strict than some of our competitors,” he says.

Zhao Zhanling, a Beijing lawyer who specialises in intellectual property and privacy rights, says the law is full of holes — regulations governing the creation of private credit rating systems include a list of data for which consent is required, but it does not clearly define “personal information”and there is no law about what “consent” means online.

Even the stewards of China’s big data revolution appear nervous about the implications of their plans. Wang Xiaolei, deputy director of the People’s Bank of China credit rating centre, which is set to manage the new “social credit” system, was quoted by Xinhua last year decrying the lack of legal protection on personal data in China.

“Think about it: personal information would be floating around all over the place, and the individual would be uninformed about any of it,” she says. “Wouldn’t that be quite scary?”

Additional reporting by Ma Fangjing

Rules for the web in China: avoid browsing late at night, do order curtains for your office, and when shopping, opt for the scuba gear over camera equipment.

Why? It all has to do with your credit rating.

沒有留言:

張貼留言