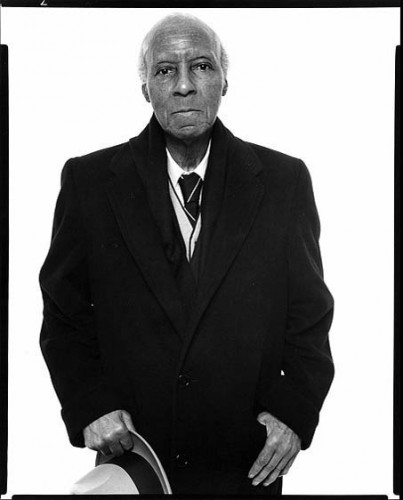

photo by Richard Avedon A. Philip Randolph (The Family) 1976

By Monica Brown. Published on September 10, 2012.

A. Phillip Randolph, Founder, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, New York City, April 8, 1976

Richard Avedon American

Richard Avedon (May 15, 1923 – October 1, 2004) was an American fashion and portrait photographer. An obituary published in The New York Times said that "his fashion and portrait photographs helped define America's image of style, beauty and culture for the last half-century".[1]

我很訝異,照片當年2004,他過世了

Richard Avedon

| |

|---|---|

Avedon in 2004

| |

| Born | May 15, 1923

New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | October 1, 2004 (aged 81)

San Antonio, Texas, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | The New School for Social Research |

| Spouse(s) |

Doe Avedon

(m. 1944; div. 1949)

Evelyn Franklin

(m. 1951; died 2004) |

リチャード・アヴェドンRichard Avedon 、1923年5月15日 - 2004年10月1日はアメリカ合衆国の写真家。 ファッション写真およびアート写真の分野で大きな成功を収めた。 ウィキペディア

生年月日: 1923年5月15日

死亡: 2004年10月1日, アメリカ合衆国 テキサス州 サン・アントニオ

芸術作品: Francis Bacon, Artist, Paris, 4/11/79、 さらに表示 此照片可在The Richard Avedon Foundation 網站中的 The Work中找到

***

George Packer writes about Angela Merkel's progression from brilliant student to political powerhouse.

****

2020年5月中旬起的香港危機,應該是雨傘革命、反送中的總結。

隔一年再讀 How Hong Kong’s Leader Made the Biggest Political Retreat by China Under Xi By Keith Bradsher June 15, 2019

我們學到那些?

2019.6.16?

NEWS ANALYSIS

How Hong Kong’s Leader Made the Biggest Political Retreat by China Under Xi

Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam was forced on Saturday into the embarrassing position of suspending indefinitely her monthslong effort to win passage of an extradition bill.CreditVincent Yu/Associated Press

Image Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam was forced on Saturday into the embarrassing position of suspending indefinitely her monthslong effort to win passage of an extradition bill.CreditCreditVincent Yu/Associated Press

By Keith Bradsher

June 15, 2019

HONG KONG — Carrie Lam, the chief executive of Hong Kong, has a very loyal majority in the territory’s legislature. She has the complete backing of the Chinese government. She has a huge bureaucracy ready to push her agenda.

Yet on Saturday, she was forced to suspend indefinitely her monthslong effort to win passage of a bill that would have allowed her government to extradite criminal suspects to mainland China, Taiwan and elsewhere. Mrs. Lam’s decision represented the biggest single retreat on a political issue by China since Xi Jinping became the country’s top leader in 2012.

Huge crowds of demonstrators had taken to Hong Kong’s streets in increasingly violent protests. Local business leaders had turned against Mrs. Lam. And even Beijing officials were starting to question her judgment in picking a fight on an issue that they regard as a distraction from their real priority: the passage of stringent national security legislation in Hong Kong.

The risk for the Hong Kong government is that the public, particularly the young, may develop the impression that the only way to stop unwanted policy initiatives is through violent protests. With each successive major issue since Britain returned Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997, the level of violence at protests has risen before the government has relented and changed course.

As many as a million people marched peacefully a week ago against the extradition bill. But the government’s stance did not begin to shift until a smaller demonstration unfolded on Wednesday. It began peacefully until some protesters pried up bricks and threw them at police officers, and police responded by firing rubber bullets and tear gas.

A protest against police brutality and the proposed extradition law.CreditCarl Court/Getty Images

Image

A protest against police brutality and the proposed extradition law.CreditCarl Court/Getty Images

A protest against police brutality and the proposed extradition law.CreditCarl Court/Getty ImagesAt a news conference on Saturday afternoon, Mrs. Lam denied that she was acting simply to prevent further violence at a planned rally on Sunday.

“Our decision has nothing to do with what may happen tomorrow,” she said. “It has nothing to do with an intention — a wish — to pacify.”

But that assertion drew broad skepticism. Jean-Pierre Cabestan, a political scientist at Hong Kong Baptist University, said the family-friendly march a week ago was not enough to send a message.

“Without a bit of violence and political pressure on the authorities, you don’t get a thing,” he said.

Anson Chan, who was Hong Kong’s second-highest official until her retirement in 2001 and now a democracy advocate, said, “Denied a vote at the ballot box, people are forced to take to the streets to make their voices heard.”

Mrs. Lam with President Xi Jinping of China last year. One question that remains unclear is how much, if at all, Mrs. Lam consulted with anyone in Beijing before introducing the bill.CreditFred Dufour/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Image

Mrs. Lam with President Xi Jinping of China last year. One question that remains unclear is how much, if at all, Mrs. Lam consulted with anyone in Beijing before introducing the bill.CreditFred Dufour/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Mrs. Lam with President Xi Jinping of China last year. One question that remains unclear is how much, if at all, Mrs. Lam consulted with anyone in Beijing before introducing the bill.CreditFred Dufour/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images[Read about the reactions of protesters, civil rights groups and others to the suspension of the bill.]

In the first years after Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, the government tended to be more responsive. A previous government had given up passing national security legislation in 2003 after 500,000 people marched peacefully.

That march was so tame that not a single person was arrested and the staff at an Van Cleef & Arpels jewelry store at the end of the protesters’ route did not close their steel security shutters or even remove the extremely expensive diamond jewelry from the store’s windows.

The extradition bill debacle underlines Beijing’s central dilemma in Hong Kong. It wants to retain complete control, and so does not want to allow full democracy in the semiautonomous territory.

But without democracy, a succession of Hong Kong governments have blundered into political crises by underestimating or ignoring the public’s concerns — and each time, Beijing gets some of the blame. Some of her close advisers say that it is unclear whether she had any discussion with Beijing leaders in advance about the extradition bill.

Demonstrators clashed with riot police outside the Legislative Council building on Wednesday.CreditLam Yik Fei for The New York Times

Image

Demonstrators clashed with riot police outside the Legislative Council building on Wednesday.CreditLam Yik Fei for The New York Times

Demonstrators clashed with riot police outside the Legislative Council building on Wednesday.CreditLam Yik Fei for The New York TimesOn Saturday, Mrs. Lam repeatedly declined to discuss her conversations with Beijing leaders.

The Hong Kong government has also proved steadily more prone to push on, at least initially, in the face of public outcry.

Hong Kong’s leaders increasingly echo top Beijing officials in perceiving malevolent foreign forces in stirring up protests. That foreign influence appears to consist of meetings that Hong Kong democracy advocates have arranged with American officials and politicians when they fly to Washington.

But Mrs. Lam and her senior advisers have nonetheless distrusted the sincerity of the protesters.

“The riots I believe were instigated by foreign forces and it is sad that the young people of Hong Kong have been manipulated into taking part,” said Joseph Yam, a member of Mrs. Lam’s Executive Council, the territory’s top advisory body.

Suspicions of foreign influence make Saturday’s retreat by Mrs. Lam even more surprising. But the path to this week’s public policy fiasco really appears to have begun last November.

That was when Mrs. Lam and her top aides traveled to Beijing for a rare meeting with Mr. Xi. He gave a long speech telling them to safeguard national security, according to a transcript released by the official Xinhua news agency.

Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng spoke to media about the extradition law at the Legislative Council Hong Kong in April.CreditVincent Yu/Associated Press

Image

Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng spoke to media about the extradition law at the Legislative Council Hong Kong in April.CreditVincent Yu/Associated Press

Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng spoke to media about the extradition law at the Legislative Council Hong Kong in April.CreditVincent Yu/Associated PressThe speech included what looked like a message that Hong Kong could not postpone indefinitely its legal duty under the Basic Law, its mini-constitution, to implement national security laws against sedition, subversion, secession and treason.

“Compatriots in Hong Kong and Macau should improve the systems and mechanisms related to the implementation of the Constitution and the Basic Law,” Mr. Xi said.

But the 2003 experience underlined how hard it would be to pass national security legislation. Mrs. Lam was also deeply troubled last winter by another issue.

She had received five letters from the parents of a young woman who was slain in Taiwan, allegedly by her boyfriend who then returned to Hong Kong. The absence of an extradition arrangement between Hong Kong and Taiwan, an island democracy that Beijing regards as part of China, complicated the extradition of the young man.

[Read about the murder in Taiwan that led Mrs. Lam to introduce the extradition bill.]

Mrs. Lam decided that a short bill — just 10 articles — should be introduced in the legislature to make it easier to extradite people.

Hunger strikers demonstrate near the Legislative Council on Saturday.CreditCarl Court/Getty Images

Image

Hunger strikers demonstrate near the Legislative Council on Saturday.CreditCarl Court/Getty Images

Hunger strikers demonstrate near the Legislative Council on Saturday.CreditCarl Court/Getty ImagesThe bill was brought to a meeting of the Executive Council, a top advisory body, right before a three-day Chinese New Year holiday, and was approved with virtually no discussion, said a person familiar with the council’s deliberations who insisted on anonymity.

The council consists of the government’s ministers plus 16 business leaders and pro-Beijing lawmakers. A holdover from the colonial era, the council is often criticized as an insular group with little to no accountability.

The week after the holiday, Mrs. Lam promptly announced the legislation.

But the bill also called for police to provide what is known in legal jargon as “mutual legal assistance in criminal matters.” Hong Kong’s top finance officials and leading financiers, who were at the meeting right before Chinese New Year, had not been alerted that the extradition bill would also allow mainland security agencies to start requesting asset freezes in Hong Kong.

They were appalled when they learned that this was involved, said the person with a detailed knowledge of the meeting. Mr. Yam did not discuss the council meeting but other people familiar with the meeting did so on condition of anonymity because of rules banning disclosure of the council’s activities.

Mrs. Lam’s bill exposed not only Hong Kong citizens to extradition to the mainland but also foreign citizens. That horrified the influential chambers of commerce that represent the West’s biggest banks, which almost all have their Asia headquarters in Hong Kong, as well as some of the West’s biggest manufacturers, which keep staff in Hong Kong while overseeing factories on the mainland.

The business community began pressing for a halt to the extradition bill. With the government having now stopped consideration of that bill, even Mrs. Lam’s allies in Hong Kong say that she almost certainly does not retain enough political capital to pass the national security legislation that Beijing really wanted.

Shortcomings in the Hong Kong government’s handling of the extradition issue underline that the chief executive is only accountable to Beijing. Yet Beijing has also promised Hong Kong a “high degree of autonomy.”

The Communist leadership likes the political structure because it ensures the loyalty of the Hong Kong government, and it rebuffed protesters who demanded free elections five years ago. But the system means Hong Kong’s leader often misreads and sometimes ignores public opinion and operates with limited feedback even from Beijing.

“Had the chief executive been elected by Hong Kong people instead of by Beijing, perhaps he or she would not have tabled that bill,” Mr. Cabestan said.

Keith Bradsher was the Hong Kong bureau chief of The New York Times from 2002 to 2016. He is now the Shanghai bureau chief. Follow him on Twitter, @KeithBradsher.

A version of this article appears in print on June 16, 2019, on Page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: In Hong Kong, Leader Yields To the Streets. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Related Coverage

Hong Kong Protest Live Updates: Thousands Take to the StreetsJune 16, 2019

OpinionYuen Ying Chan

Why Hong Kong Will Still March on SundayJune 15, 2019Hong Kong’s Leader, Yielding to Protests, Suspends Extradition BillJune 15, 2019

Carrie Lam: A ‘Good Fighter’ in the Crisis Over the Hong Kong Extradition BillJune 14, 2019

沒有留言:

張貼留言